Before the Black Panther: The First Black Comics Heroes—plus Two Early White Heroes with Black Mentors

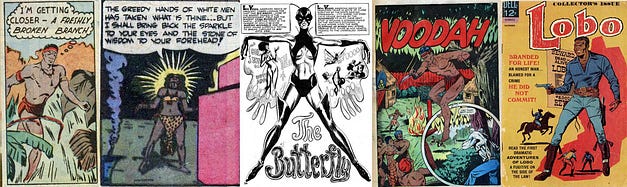

While there were many Middle-Eastern heroes in the early days of comics (perhaps because Middle-Easterners had been legally white since 1909), black characters tended to be assistants or comedy relief or both. The most famous—or egregious—examples:

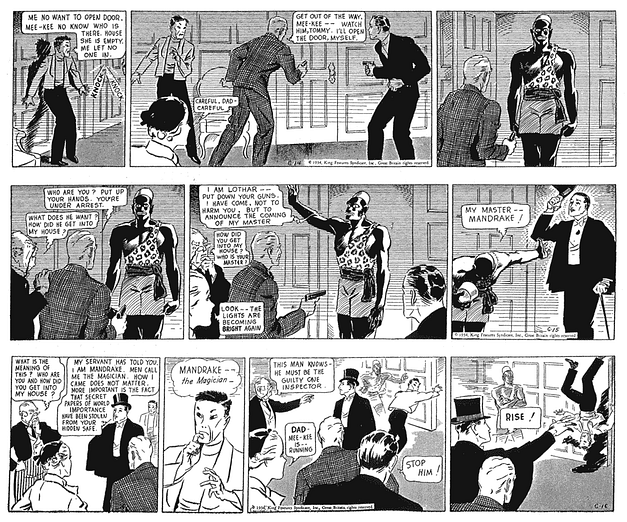

- Lothar, created in 1934 as a servant for Mandrake the Magician.

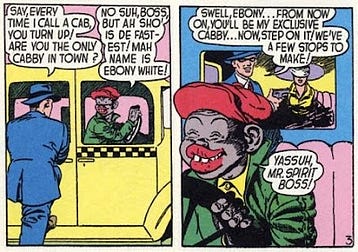

2. Ebony White, created in 1940 as the Spirit’s friend and aide.

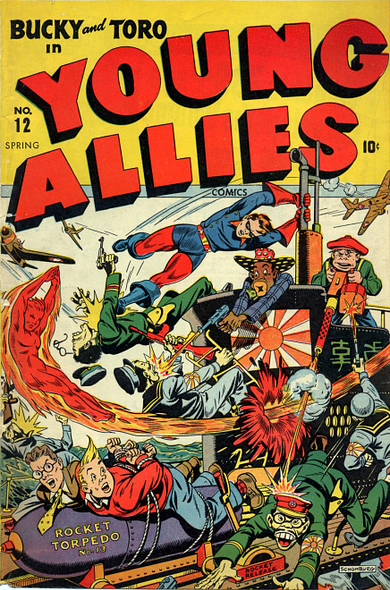

3. Whitewash Jones, created in 1941 as a member of the Young Allies.

4. Steamboat Bill, created in 1942 as Captain Marvel and Billy Batson’s valet.

There’s little good to be said about Whitewash and Steamboat. Marvel Comics eventually addressed the depiction of the Young Allies in the only way possible by saying those comics were wartime propaganda and not part of official Marvel continuity. Steamboat was so offensive that an integrated group of students visited Captain Marvel’s publisher in 1945 and convinced them to stop using the character.

But Lothar and Ebony had black fans who liked them because they were generally capable characters who were respected by their bosses. Lothar calling Mandrake “master” makes some readers think Lothar was a slave, but there’s nothing racial about “master”—that’s what servants called their bosses and Igor called Dr. Frankenstein.

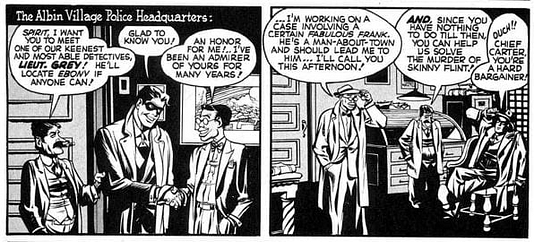

Ebony is the most controversial of the four—drawn in the minstrel tradition with heavy-handed ethnic dialogue, he’s both a comic figure and a competent friend who sometimes saves the Spirit. Criticism of Ebony may have prompted Will Eisner in 1947 to create Lt. Grey, a contender for the first black detective in comics. Sadly, Grey never became a fulltime member of the cast.

Even the most enlightened comics creators faced a hard fact: Jim Crow ruled in the South and many forms of discrimination were still common in the North, so publishers were afraid they could not sell stories starring black characters. Yet in 1936, shortly after the success of the Phantom newspaper strip, the Red Mask ran for several months as a Sunday color strip.

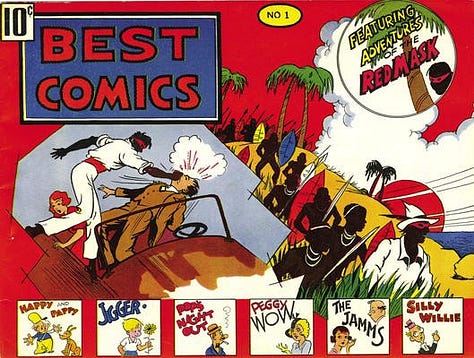

The Red Mask may be the strangest creation in the history of race and superheroes. Whether he was a black man or a white man passing as black, we cannot know because contradictory clues were given and his identity was never revealed. (For more about him, see The Mysteries of the Red Mask, the First Black Masked Comics Hero.) After his newspaper run ended, the strips were reprinted in 1939 in four issues of Best Comics. On the cover of the first book, he looks black. On the covers of the last three, he looks white but stays black on the inside pages. I would love to know if any readers complained.

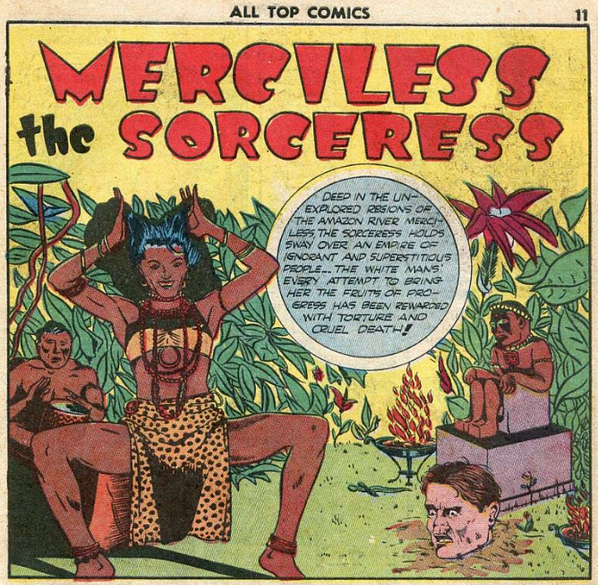

Changing the Red Mask’s race on the cover but not the inside of his book reveals a truth about racism and comics: the great obstacle was not with readers but with distributors, shop owners, and self-appointed guardians of decency who glanced at a cover and decided whether to condemn it. Which explains why the few interesting black characters appeared inside comics but not on their covers. Case in point: Merciless the Sorceress in All Top Comics in 1944.

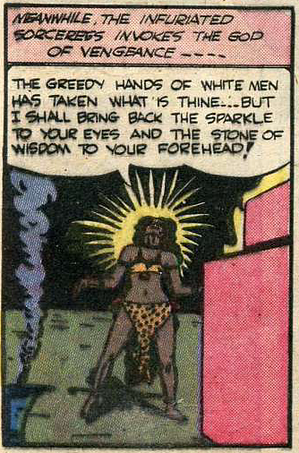

She’s written as a villain, but I like to think of her as the first black female superhero—she has magical powers, she uses a pseudonym, and she seeks justice under her terms. When jewels belonging to her tribe are stolen by a white man, she sets out to get them back. The following panel shows some sympathy for her cause:

Sadly, her four-page story was never completed. Later stories using her name are about a white woman who lives in the far North.

If I had the job of reviving Merciless, I’d make her an African shapeshifter who can look like the locals wherever she goes.

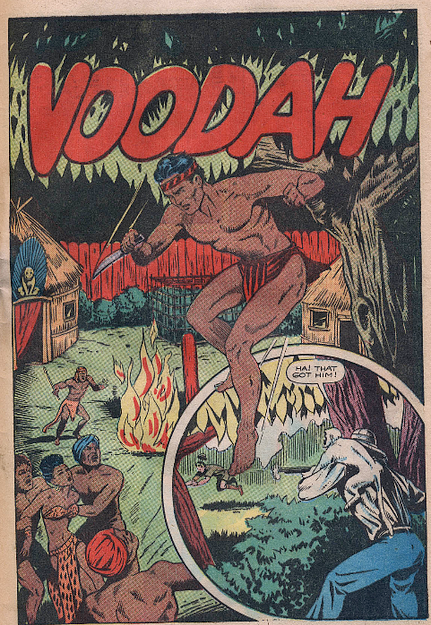

The first unambiguously black comic book hero to have his own series was Voodah, who appeared in 1945 in Crown Comics #3.

But Voodah was only unambiguously black for three adventures before he was white-washed more thoroughly than the Red Mask had been. When he made the cover of Crown Comics in issue #5, he was colored white even though he stayed black in his story. Beginning with the next issue, Voodah was always given lighter skin than the natives.

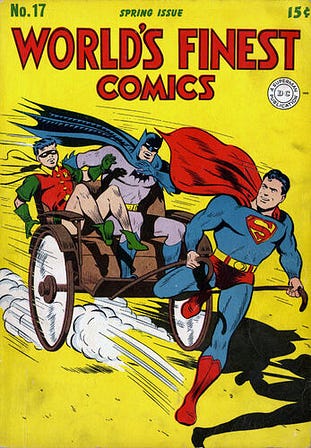

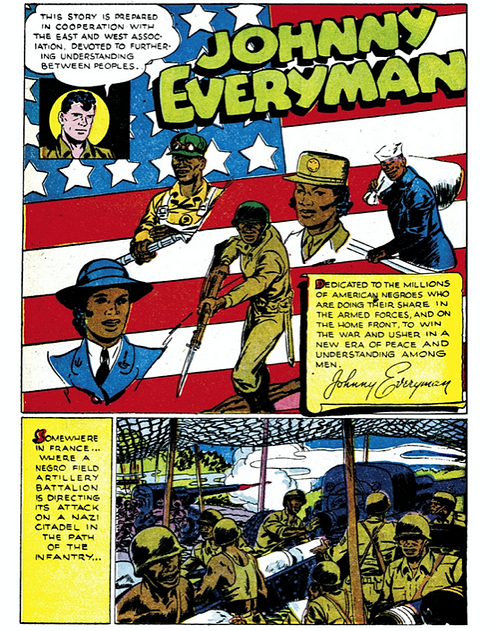

Despite Voodah’s setback, 1945 was an important year for black comic book characters. That’s when Captain Marvel dropped Steamboat from the cast. And in the “Johnny Everyman” strip in the back of World’s Finest #17, DC comics tackled prejudice directly by creating Ralph Jackson, who many of us call DC’s first black hero.

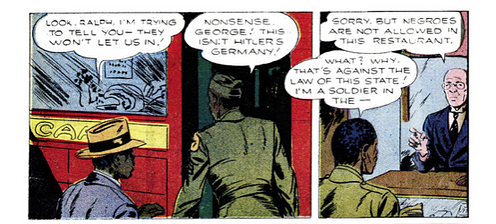

In the first pages, the black soldiers are established as war heroes. Then Jackson returns to the US and faces a problem that was much too common:

The story ends with Johnny Everyman assuring Jackson that things are slowly getting better. You may say Johnny’s a white man who’s patronizing an understandably outraged black man, and I’ll agree, but he’s also a white character who is showing Superman and Batman fans that black and white people are equally deserving of respect.

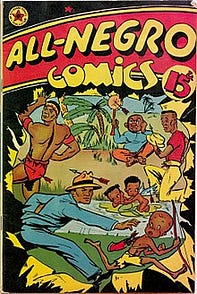

In 1947, some black comics fans decided to tackle the problem of black representation in comics with their own book, All-Negro Comics.

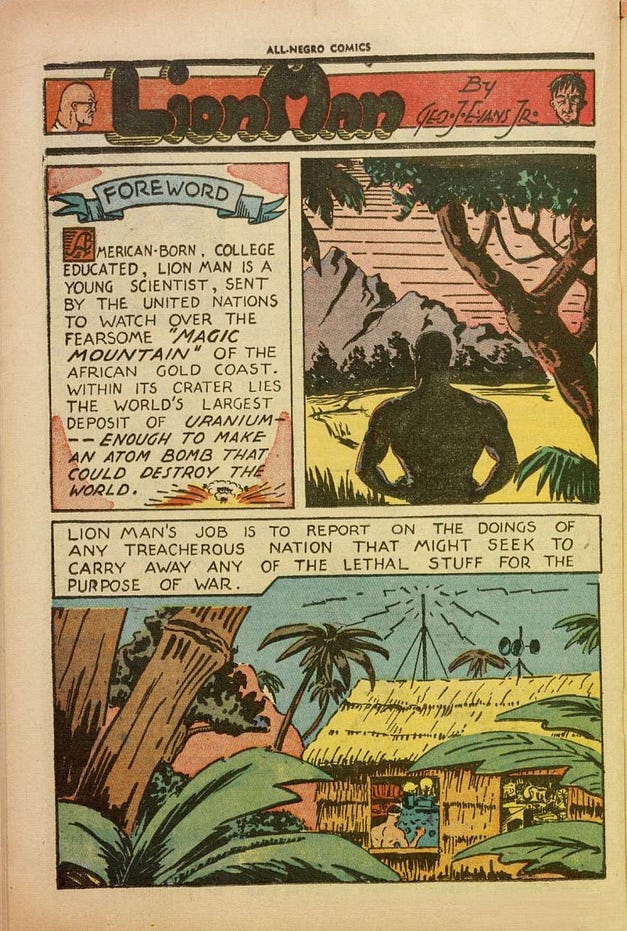

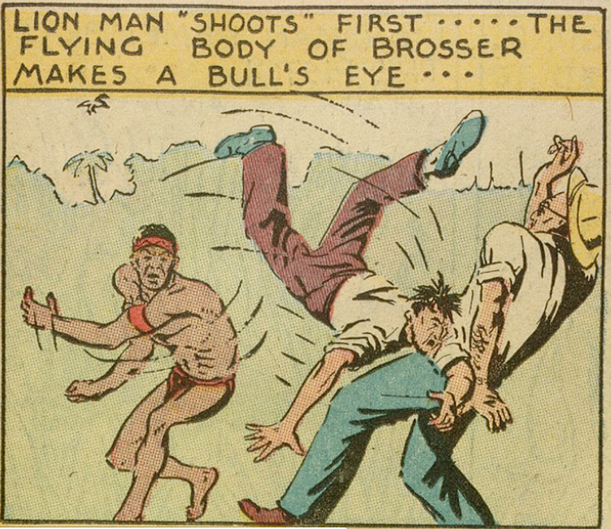

In one strip, they merged the jungle hero and the science hero to create Lion Man:

The villains are white men. Lion Man defeats them with ease.

All-Negro Comics is a charming anthology, no more crudely written and drawn than many other comics of the time. But the racist marketplace did not support it.

Jeet Heer makes an important observation about what happened as comics creators faced criticism:

Paradoxically, the civil rights agitation of the 1940s didn’t just lead to the disappearance of offensive stereotypes, but to a larger ethnic cleansing of the comics. With publishers and cartoonists afraid to offend black readers, characters like Li’l Eight Ball and Ebony White disappeared. But they weren’t replaced, except in a few cases, by non-racist black characters (who might have offended racist white readers). Instead the comics sections of the 1950s became very lily-white, with far fewer non-white characters than before. There are exceptions: Walt Kelly’s character Bucky in the Our Gang stories and a black boy briefly introduced in 1942 in Little Orphan Annie.

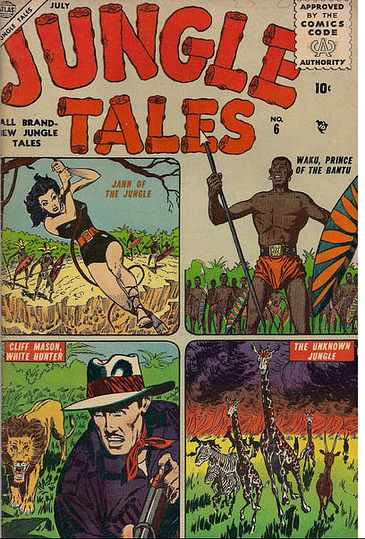

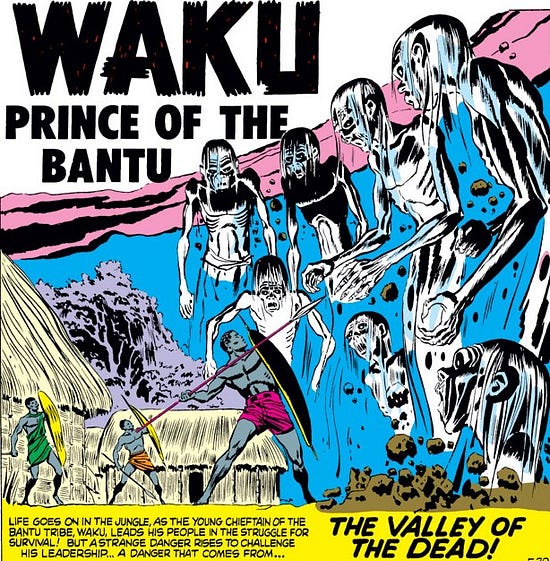

Among the exceptions was Waku, Prince of the Bantu, who, in 1954, began leading his people wisely and bravely.

Jungle Tales was published by the company now known as Marvel. For seven issues, it tried to offer more than Tarzan clones to its readers. Then the editors saw where the money was and changed the book’s title to Jann of the Jungle, where Waku made his eighth and final fight.

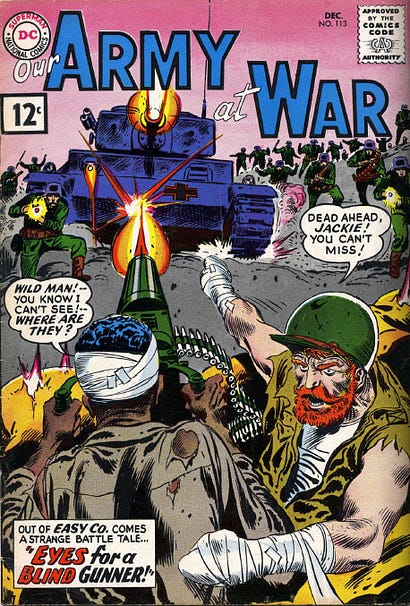

In 1961, DC Comics published Our Army at War #113, making Jackie Johnson its second black war hero and the first to be a member of an on-going series.

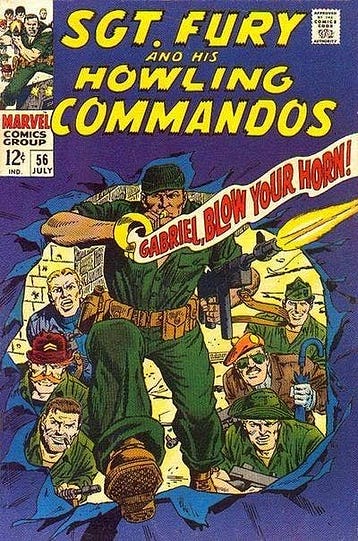

In 1963, Marvel followed suit. Gabriel Jones, a founding member of Sgt. Fury’s Howling Commandos, sometimes got his moment in the spotlight.

The next interesting attempt at creating a black hero came in Mask and Cape #4, a comics fanzine published in 1964. The Black Phantom was a black man with a white sidekick who fought the Ku Klux Klan. The general public would never have seen the Black Phantom, but many comics creators would. He was a reminder that the field had tried black jungle heroes and black war heroes, but it had not tried a black superhero since the Red Mask’s day.

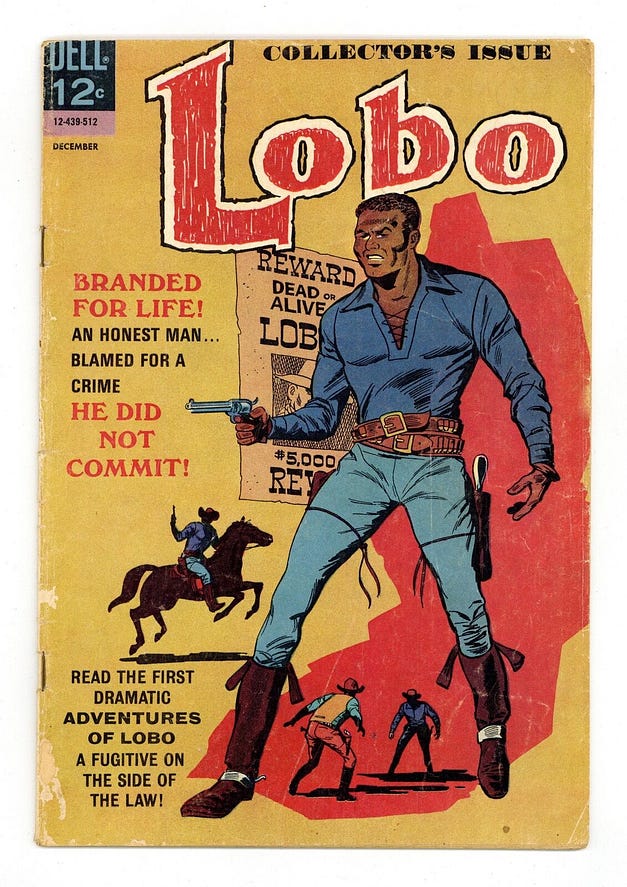

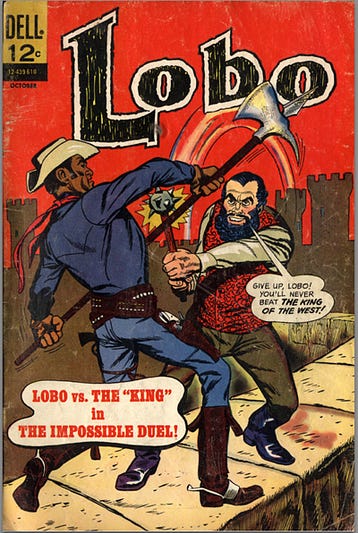

1965 brought the first black hero who headlined a comic and the first major black western hero. A former Union soldier, Lobo fought the good fight for two issues.

Tragically, Dell Comics tried to do a good thing before comics distributors were ready. According to COMICS WITH PROBLEMS:

…when it came time for distributors to return the unsold copies, the publisher found most had never been put out for sale. In fact, they hadn’t even been taken out of the box. Distributors shied away from the product just because it had a black man alone on the cover, tho except for his skin color, no notice was made of the fact, there or throughout the issue. Over 90% of the print run came back.

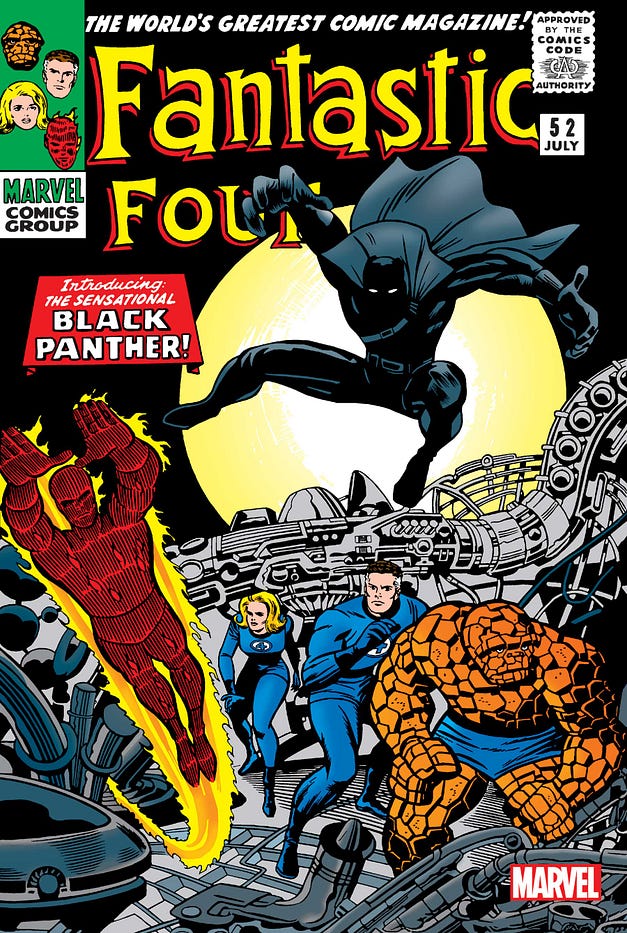

But the industry’s resistance to black heroes began to crack just one year later. In 1966, Jack Kirby and Stan Lee created the Black Panther and ushered in a new age of comic book heroes.

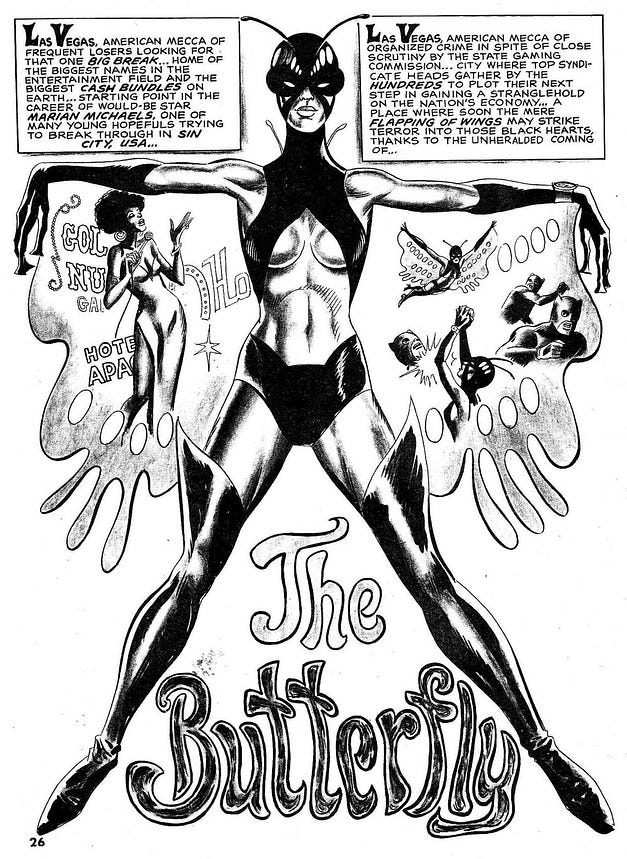

Bonus #1: the first black female superhero

If you disagree with me that Merciless the Sorceress was the first black female superhero—and you probably should—then who was?

Butterfly. She appeared in 1971 in Hell-Rider #1, a black-and-white magazine with national distribution.

Bonus #2: Two white heroes who inherited magical artifacts from black heroes

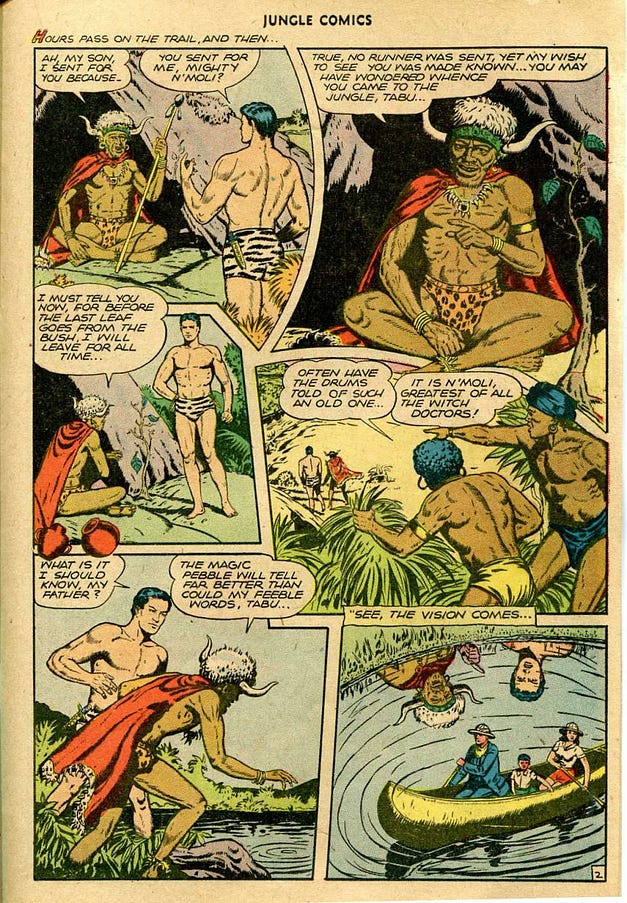

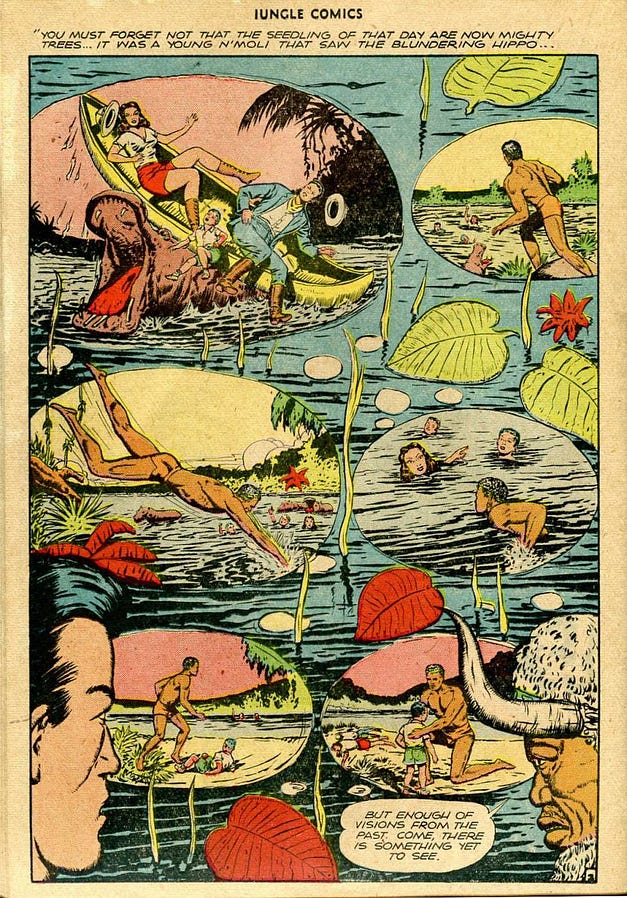

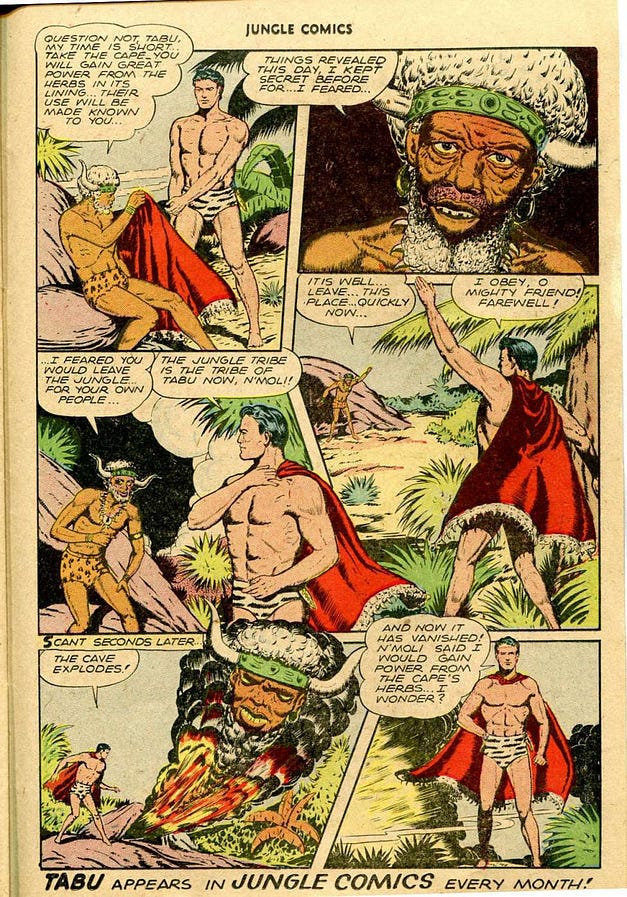

In a genre filled with oddities, Tabu, who first appeared in 1940 in Jungle Comics, was one of the oddest: What happens if you combine a jungle hero with a magician?

Tabu got his training and his cape from a black mentor who clearly had the mystical protector gig before him.

When the witch doctor is fatally wounded, he passes his legacy on to his adopted son.

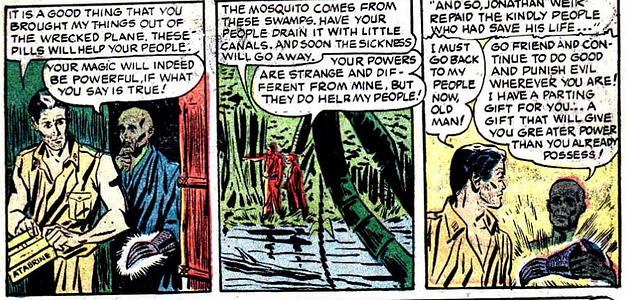

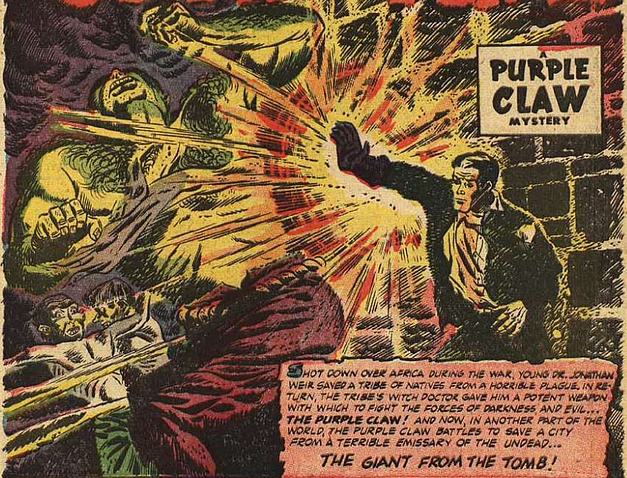

There’s a similar explanation for the Purple Claw, who starred in a book of the same name in 1953. Dr. Weir crashed in Africa and was nursed back to health by the locals. When malaria struck the tribe, he was able to save the people. To thank him, the elderly wearer of the Purple Claw passed it on to him.

In both cases, the Africans are treated respectfully. If I was to revive Tabu or the Purple Claw, I’d create a new black character who would inherit the name and the artifact from the white man who had been entrusted with them.

Comments

Post a Comment