On Indiana Jones and a 1951 comic book that did race and gender better

When the Indiana Jones movies were released, I loved Raiders of the Lost Ark, hated The Temple of Doom, thought The Last Crusade was slight, and had no interest in seeing The Kingdom of the Crystal Skull so I skipped it.

Recently, I’ve been watching action movies while I exercise, so I decided to revisit Indiana Jones. I found Raiders of the Lost Ark holds up well. Marion Ravenwood is, like Indy, tough and competent. Sallah, Indy’s Egyptian friend, is fully capable in his own right, and so is a black supporting character, Simon Katanga, the captain of a cargo ship that’s attacked by Nazis. Ravenwood, Sallah, and Katanga feel like they had adventures before Raiders began and would have more after it ended.

But the credit for the respectful treatment of those characters must go to Lawrence Kasdan, Raiders’ primary writer. The Temple of Doom seems every bit as sexist and racist today as I remembered it when it was released: The only significant female character is incompetent, vain, and stupid. Short Round, the Asian kid sidekick, is mostly there to be cute. The primary villain is an Indian who opposes the British Raj. The story ends with British soldiers arriving at the last minute to kill the brown rebels and restore Britain’s idea of peace.

If you think the plot choices are reasonable for a movie set in India in the 1930s, remember that Gandhi began working for independence in 1915. Lucas and Spielberg are film buffs — they should have remembered the lesson of movies like The Seven Samurai: we want the people who are threatened to save themselves in the final battle.

And they should have remembered the female action characters from the old action movies they loved, like Pauline Hargraves, Torchy Blane, and the Black Whip. The Temple of Doom could’ve been about Indy, with the aid of a competent love interest and an Indian friend, thwarting Nazis or a British imperialist like Sir Oswald Mosley, leader of the British Union of Fascists. Instead, it’s so casually racist and sexist that it might’ve been written at the height of the Jim Crow era.

Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade does better in terms of race and gender, but only by omission: it’s a buddy picture about Indy and his dad. Its only important female character is capable but not admirable. Sallah returns, but he’s not nearly as interesting or as significant as he was when Kasdan wrote him. This movie’s all about the white guys, the Jones father and son team.

The sexual politics of the series improve in The Kingdom of the Crystal Skull: Marion Ravenwood returns and the main villain, Colonel Spalko, is female, but this movie tries harder to be a comedy than an adventure story, so all the characters are written for cheap laughs. Spalko is not half as interesting as Belloq in Raiders and Marion is not half as interesting as, well, Marion in Raiders.

As for the racial politics, there are no significant characters of color. New characters like Mac and Mutt are white. Characters from previous movies like Sallah, Short Round, and Katanga do not even make token appearances, which is especially noticeable in the marriage scene. Indiana Jones, world traveler, appears to only have white friends.

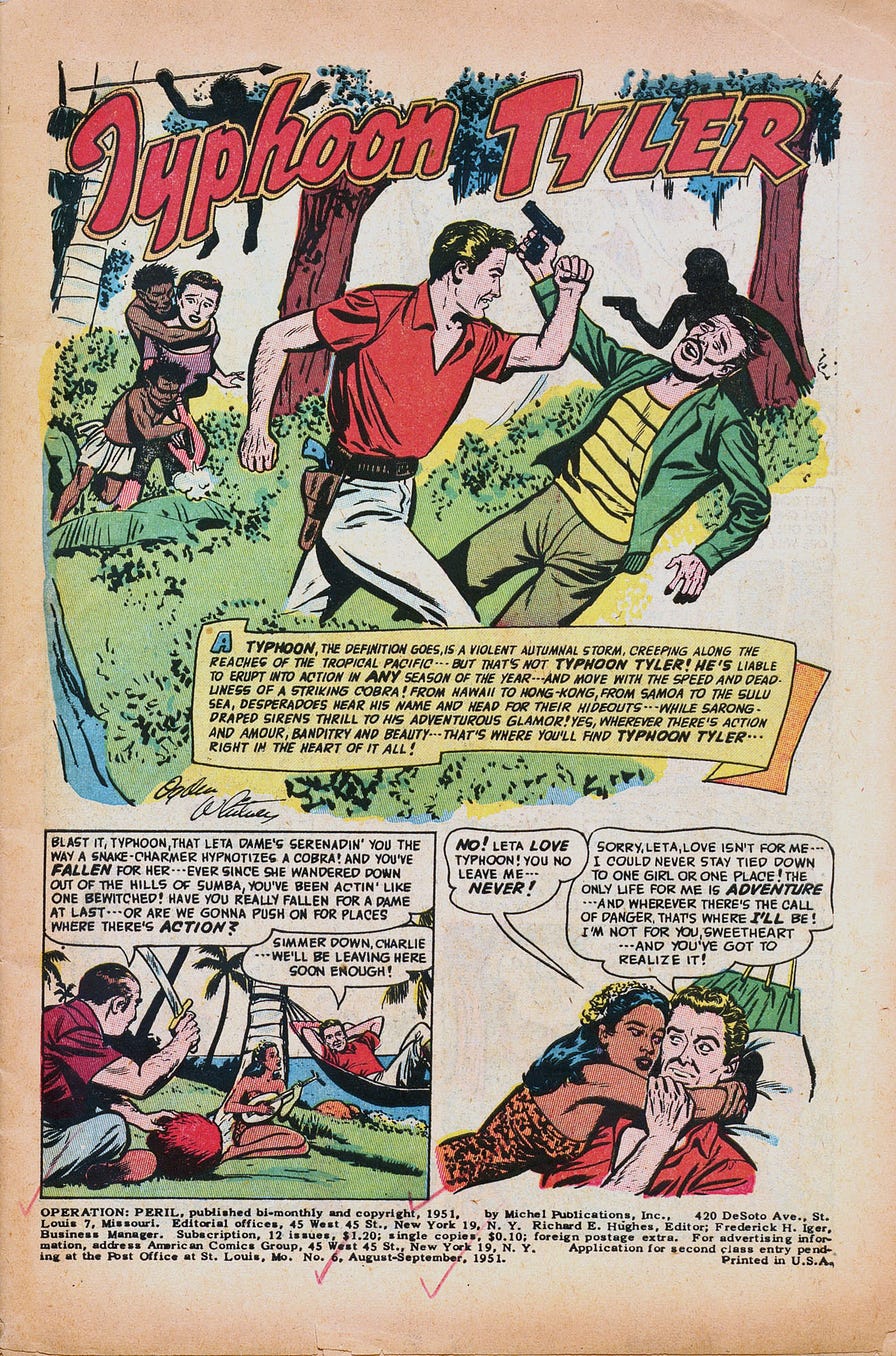

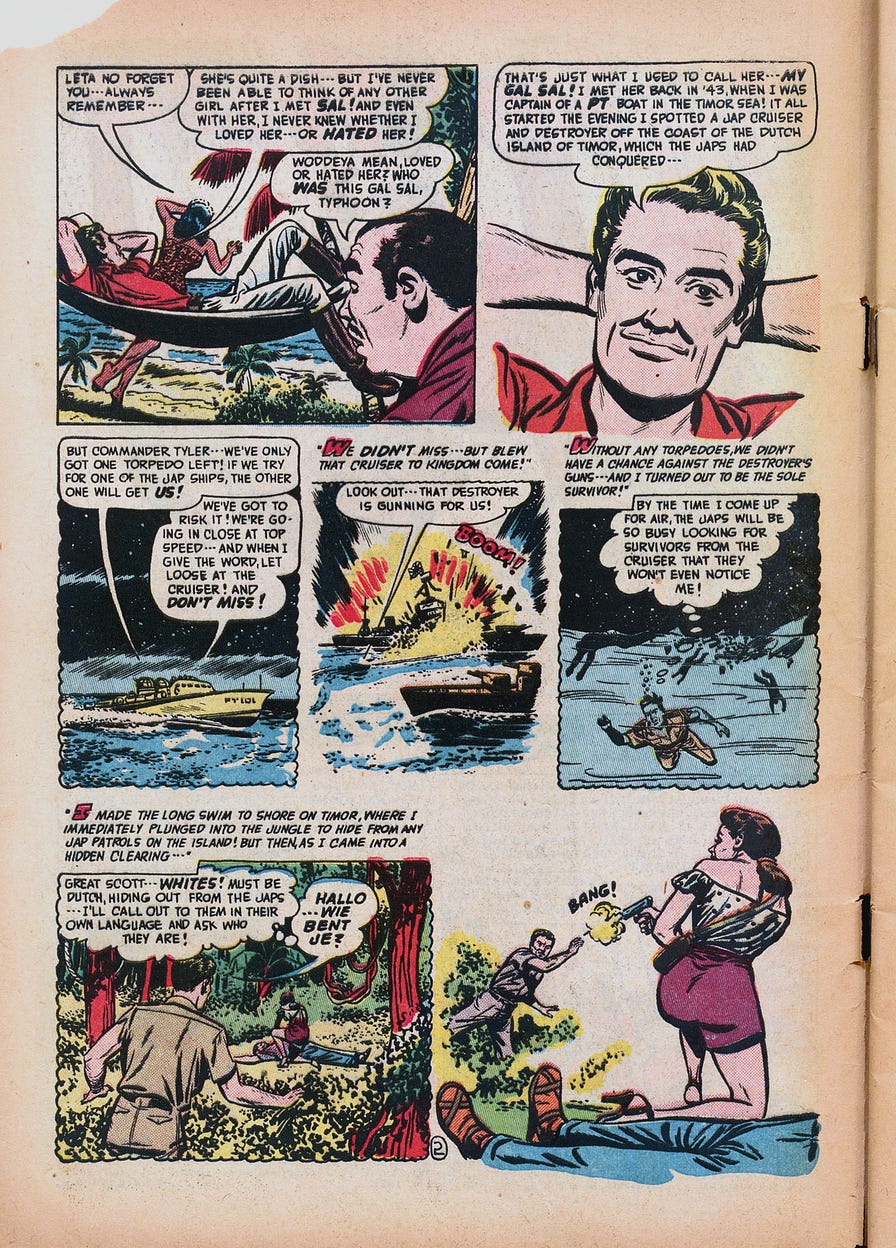

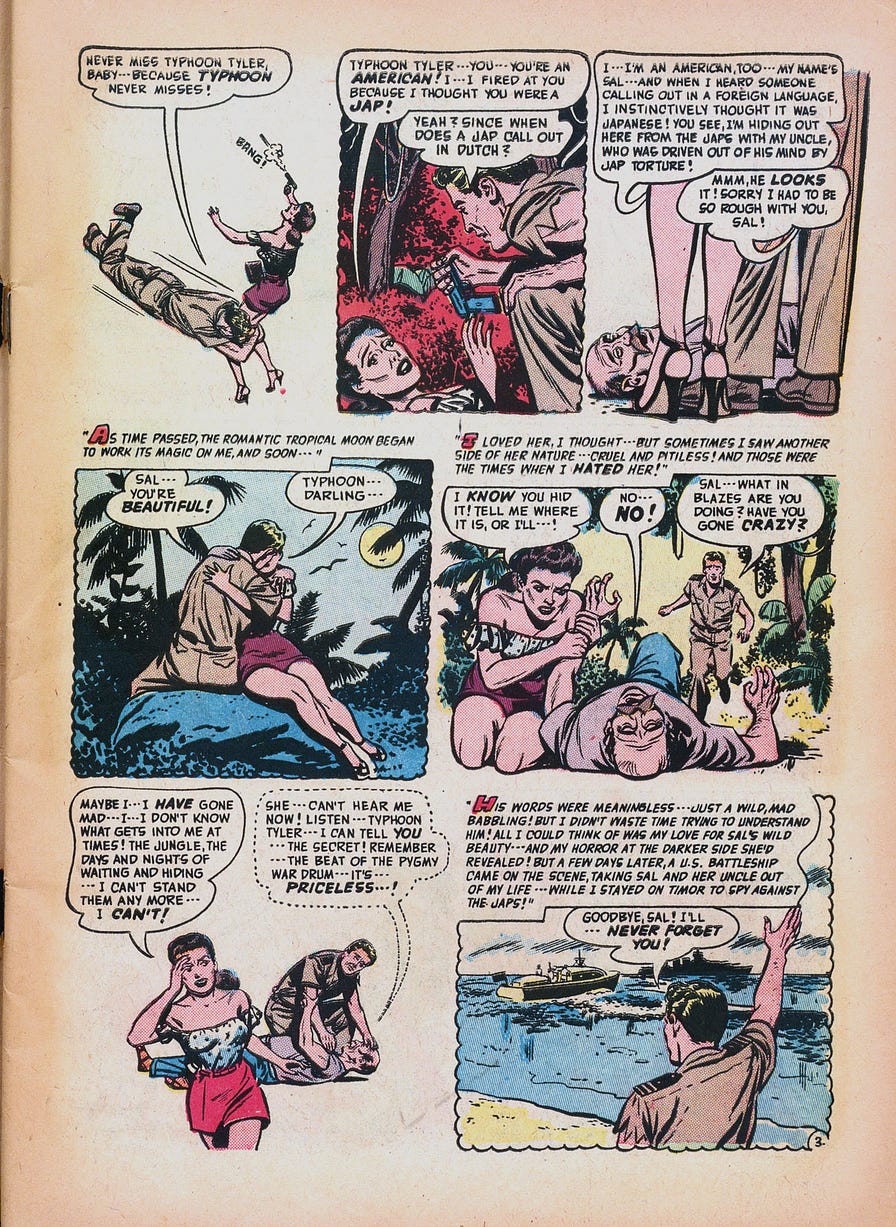

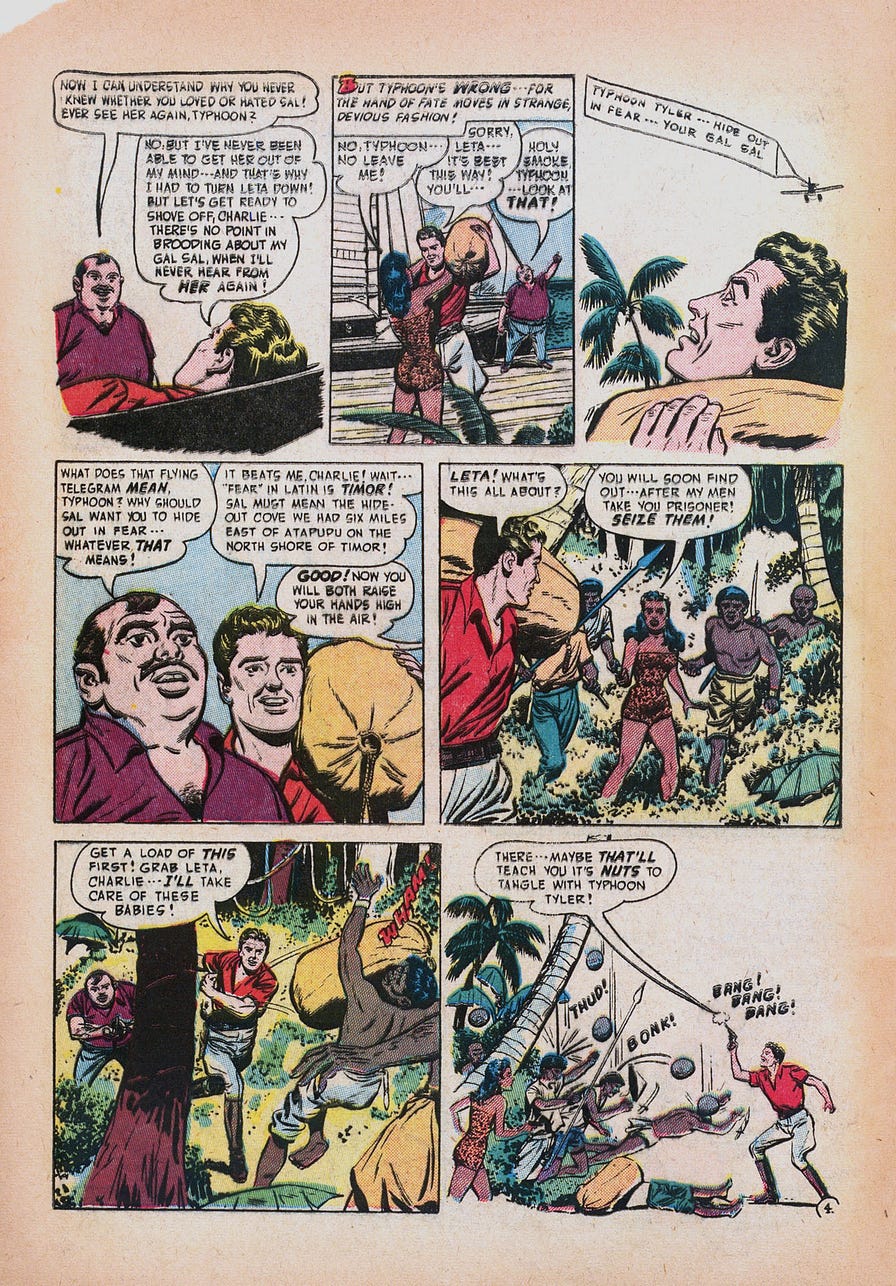

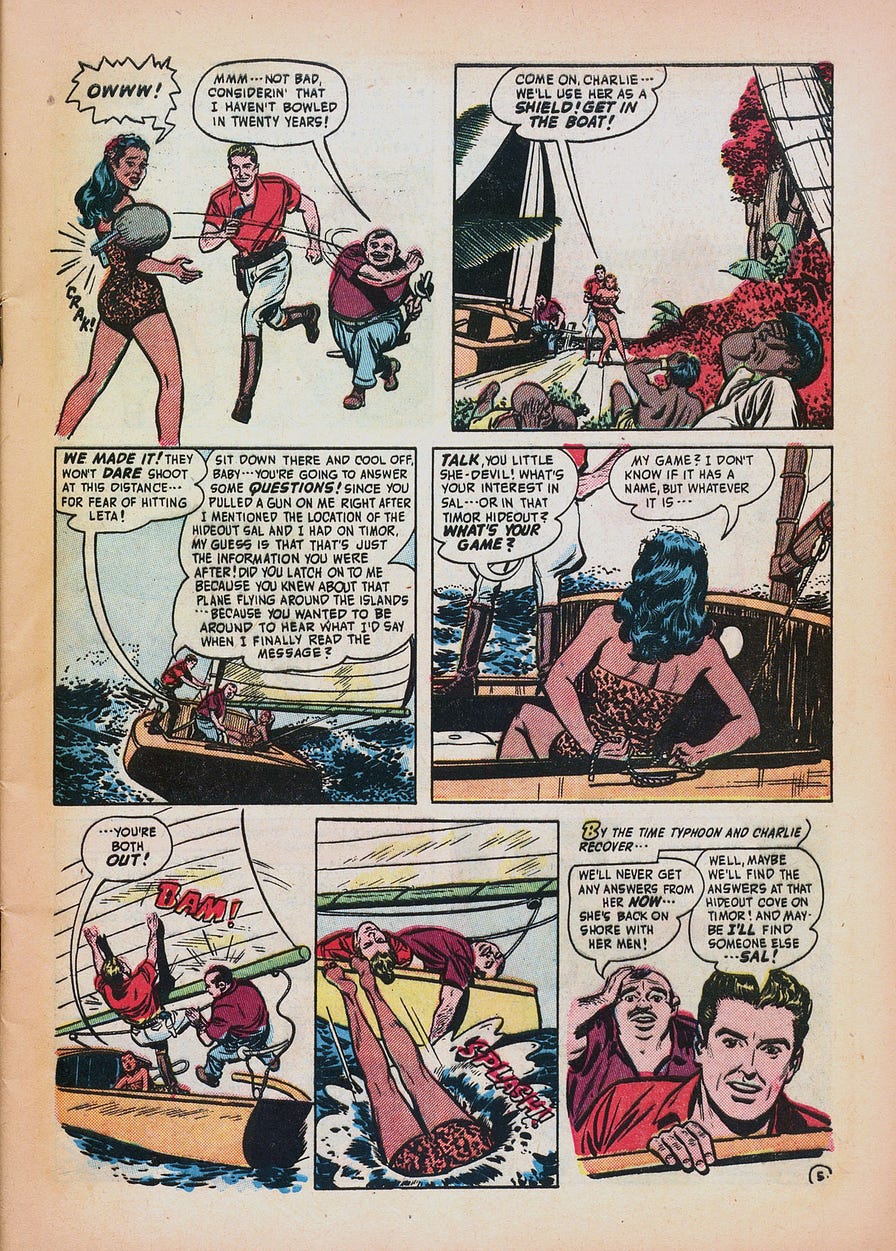

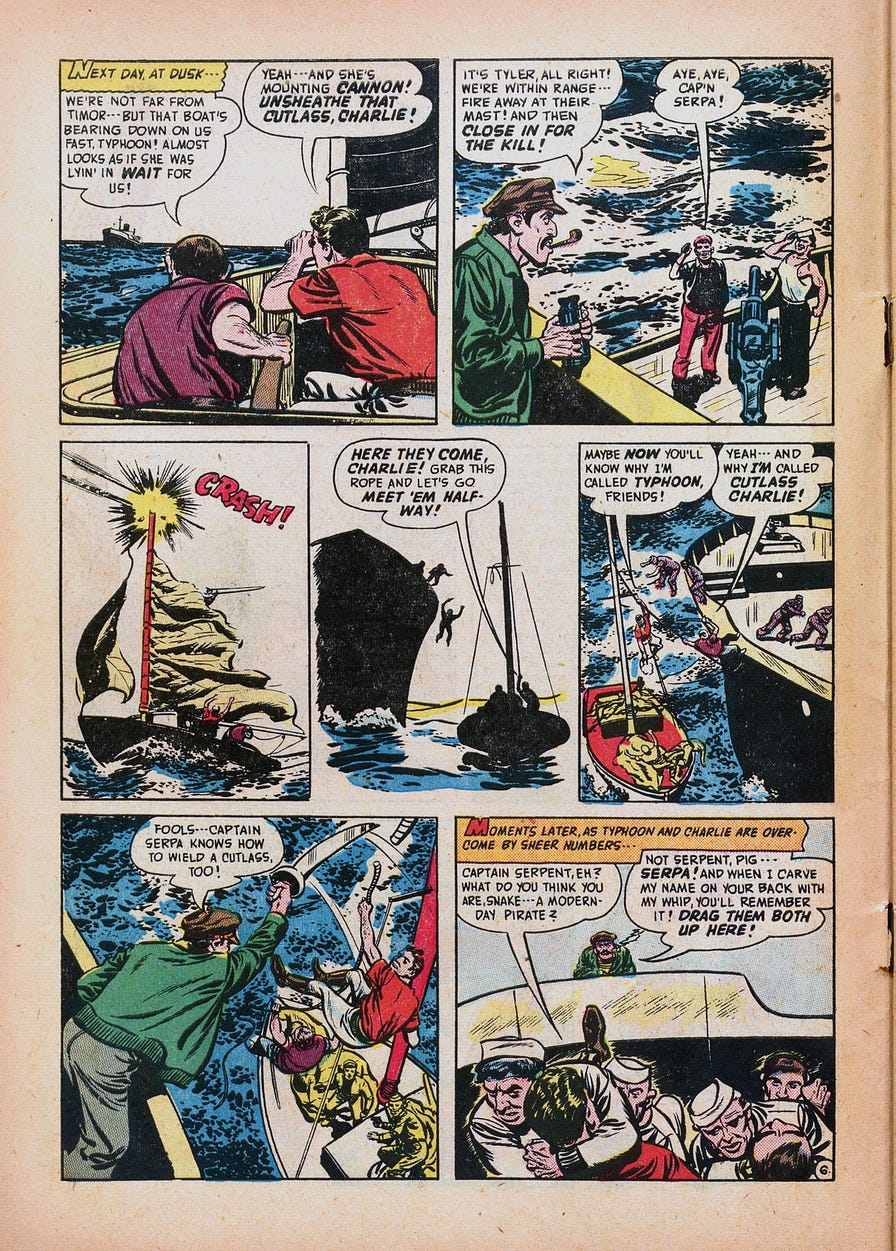

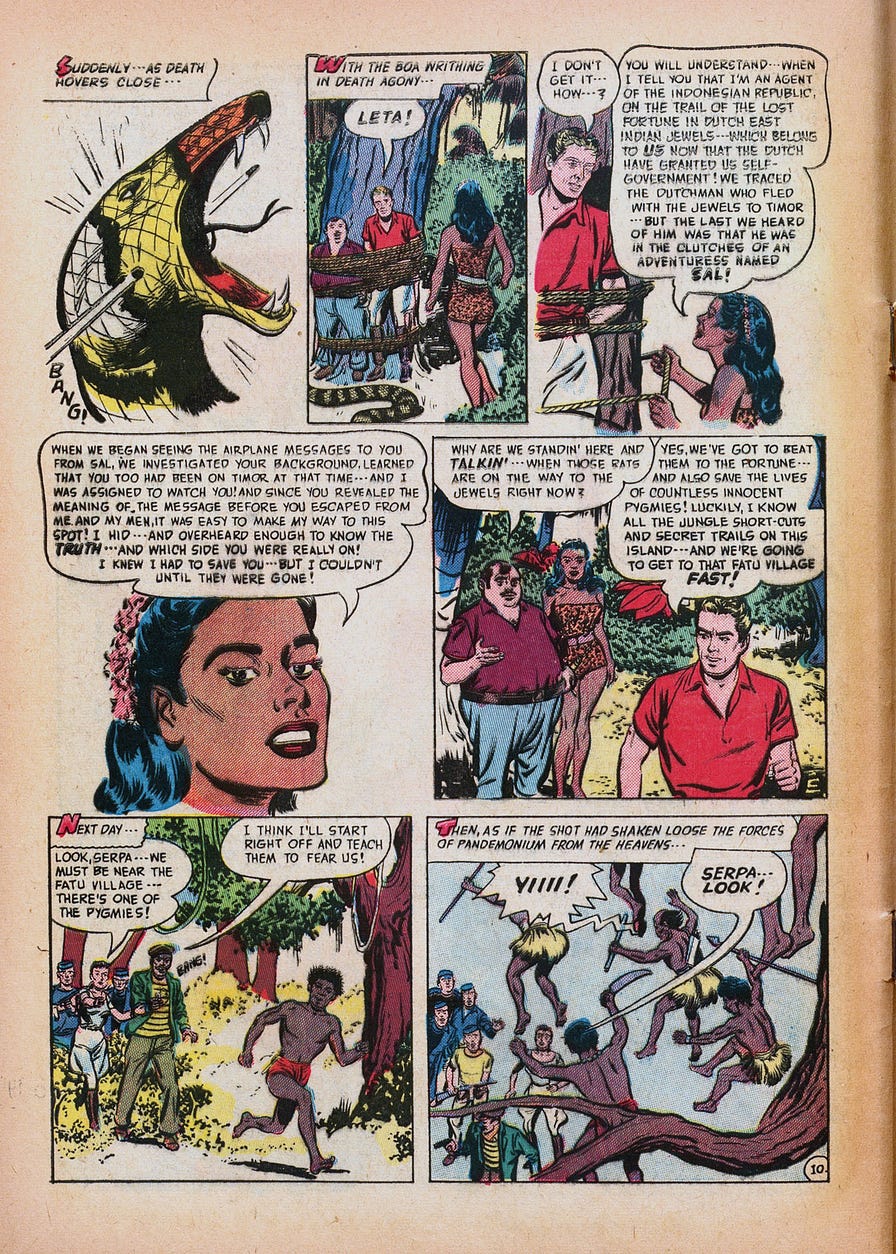

You might think some sexism and racism are to be expected in material based on old adventure stories. But if you do, consider the following story from Operation: Peril #6, a 1951 comic. Leta is not what she appears to be at the beginning or the middle. Since I hate spoilers, I’ll make my final comments after sharing the original short comic.

One warning: This is not great art. It was probably written in a day. Yet it has virtues that are missing from the later Indiana Jones movies.

You may spot many shortcomings in this old comic, but don’t miss its virtues:

- Though Typhoon Tyler is a white male adventurer, he does not fall into the “white savior” trope. He alerts the locals that the bad guys are coming. Once alerted, the locals save themselves.

- There are two capable women, a white villain and a brown love interest who escapes on her own when Tyler tries to capture her, then saves him when he is trapped.

One more warning: After reading this comic, I skimmed the rest of the Typhoon Tyler stories to see if any of them were as interesting in their handling of race and gender. They’re not. My point with this little essay isn’t to make a forgotten comic strip famous. It’s only to show that the worst missteps made in the Indiana Jones movies were avoided by a comic book writer who was working in a far more racist and sexist time.

Comments

Post a Comment